A Poem a Day with Esther Cohen

Esther Cohen’s first writing job was one she created herself. While spending her childhood summers in a coastal Connecticut town, she and her best friend invented a magazine that chronicled neighborhood happenings. The two girls would circulate their handmade publication to their neighbors, who undoubtedly devoured the local gossip.

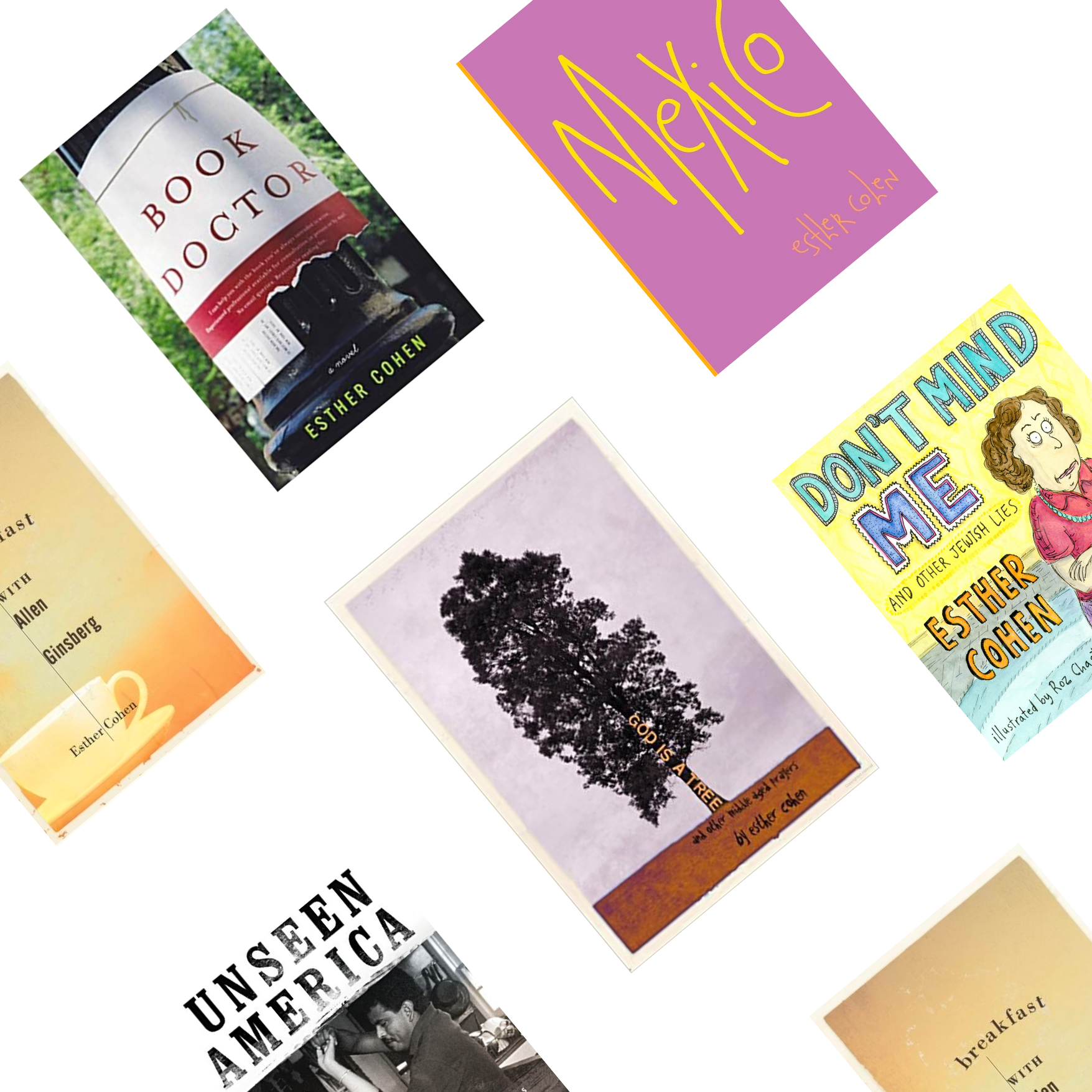

Decades and decades later, people are still hungry for Esther’s words. She’s published a bevy of books, from fiction novels to poetry collections to photography-focused titles. And she has a devoted audience that subscribes to her Substack newsletter, OverheardEC, where she posts a new poem every day.

Of all the stores that carry Esther’s books, Mast Market is the nearest to her heart—physically, at least. She lives in the same building as our Upper West Side location, so she’s become a dear member of our own community. Here, she shares what it’s like living so close by, how she became a professional writer, and what she’ll be publishing next.

Mast Journal: What is it like living in the same building as Mast Market?

Esther Cohen: I am a frequent shopper. I live in the building, so I'm pretty much there. And everyone in New York City is on the street all the time. So I go out every day and often stop in. And there's always something there that I want—besides the chocolate.

MJ: That’s amazing. What are some of your favorite things to buy?

EC: I always, always get the chocolate, but they have a lot of new stuff, too. I asked people in the store what to get, and they told me about these ginger drinks. It’s a non-alcoholic beverage that I never would've picked up and it was delicious. I take everyone's selections very seriously.

And the really nice thing is that a lot of the people who work in the store have read my books of poems, so they pretty much know what I like. I get a lot of the greens. Every single thing is so nice. They carry many kinds of fantastic pasta and I've tried them all. They also have a really nice yellow tomato sauce. Whatever anyone tells me to get, I get. And I've never been steered wrong.

MJ: We love to hear that. Are you a big cook?

EC: I would say I'm a small cook. My son is a cook. My son went to Bard and there were a lot of vegetarians there. And as a result, he started the barbecue club. He is a New York City kid and he is a little contrarian. So he started barbecuing because there were so many vegans. His barbecue club was very successful and he got into the whole food thing. He started as a sous chef at a restaurant in the village called Lupa and now he's a story producer for the Food Network. So he's a serious food person. And his wife, who's South African and directed Tina Turner on Broadway, is also a fantastic cook.

MJ: That’s so cool! Did you teach your son to cook? Or did he teach you?

EC: We have a house in upstate New York, all of us. And we all cook together all the time. We were together there in the pandemic for five months. And my husband, who's a documentary filmmaker named Peter Odabashian, made a film called My 2020 about living together in the pandemic. And cooking was one of the central things we did in the pandemic when we couldn't do much else.

MJ: That’s not a bad way to spend quarantine. When did you first start writing?

EC: As a child, we had a beach house in Milford, Connecticut, and we spent the summers there. And my best friend, whose name was Abby Glaser, and I started a handmade magazine called Gab. And it's interesting, she was the illustrator and I was the writer, and she became a photographer. She's been teaching photography at the School of Visual Arts for a million years. And I became a writer. But Gab was our first published effort. We published it. We wrote a lot about our neighbors endlessly, and then we distributed the publication to our neighbors.

MJ: How bold of you!

EC: It was. But we weren't critical. Let me just say that. We weren't criticizing our neighbors. Many of my features in Gab were about the dates of our next door neighbor. I described looking out the window, watching date X pick her up and what she wore and what he wore and what I imagined was the dialogue between the two of them.

MJ: That’s fun!

EC: Then I described the date with this guy named Harry that my mother fixed her up with and she married him. I documented the whole thing in Gab.

MJ: Wow, what a successful setup. And how did you become a professional writer?

EC: That's a question that everybody asks all the time. The way you become a writer is by writing. I just always wrote, and I always looked for places where my writing could be. I was in the Israeli Peace Corps, so I wrote a novel about it called No Charge for Looking while I was there. There was so much to write about. And I did. It took me many years to write the book, but Schocken published the book. And then I wrote some other books and that was the story.

MJ: Did you focus on fiction before you moved onto poetry? Or have you always written both?

EC: I didn't really move to poetry. I have a new book coming out in November called All of Us. The premise of the book is that we need all of us. Particularly now when we're so polarized and fractured and alienated from one another, we have to figure out a way for there to be an ‘all of us.’

MJ: So it’s non-fiction?

EC: No, it’s fiction. I’ll tell you exactly what it is. Thirty seven years ago, my husband and I and some friends bought a house in upstate New York, in a tiny little town. We looked for a solid year at houses in counties that were close to New York City. We had a realtor who was a German woman who lived in Columbia County. And we asked her if we could go to Greene County, which is where I now live, and she said, You don't want to go to Greene County. It's too wild. And I said, ‘Ah, that's exactly where we want to live.’

What she meant by ‘wild’ was there were no cheese stores, there were no bread stores. And that's where we wanted to live. We bought this house when my son was a baby. I worked from the country—I've had jobs my entire life—and my son grew up here. And I was very concerned that the people from New York City and the people who were born here were not going to be able to connect. And so the farmer's wife and I started an open house potluck here. Over a hundred people came for the first time. And since then, that's pretty much what I've been doing.

MJ: That's amazing. Have you had jobs in addition to writing?

EC: Oh yeah. For many years, I was the executive director of Bread & Roses, which is a national nonprofit for workers' culture that was connected to a labor union called 1199. I’ve run nonprofits my whole life.

MJ: What was that work like?

EC: Unseen America is a project I did at Bread & Roses. Essentially, the notion was that we gave cameras and 12-week classes with professional photographers to literally hundreds of groups of people, from nannies and migrant workers to healthcare workers and people in nail salons. We gave them the tools to tell the stories of who they were from their own perspectives. And then we had hundreds and hundreds of exhibits, including in the Department of Labor. I had a book party with a thousand workers at the Guggenheim Museum. And I did that forever and ever and ever.

Now my new book, which is called All of Us, has the same premise, but with language, in the sense that I drew a portrait of a lot of different people who were very different from one another living side by side in upstate New York. And I'm going to be running workshops that are reading-writings. So people come in, hear me read, and get the book, but they'll also write their own ‘us.’ For example, the workers at the Brooklyn Museum are going to participate and I've got a class with nail salon workers.

I've always taught writing for my whole life, too, alongside my jobs. I'm interested in teaching to groups of people who don't normally have an opportunity to take writing classes. So I teach formerly-incarcerated and incarcerated women. I teach a class with Republicans and Democrats that I've intentionally constructed. I teach older people who are part of a city senior center. I teach low-wage workers of all kinds.

MJ: That’s so cool. Do you find a lot of inspiration in New York City?

EC: Definitely. Every day I get on the subway and think, Wow, I'm so happy to be here. Growing up outside of the city, I couldn't wait to be here. I still have no appeal in living anywhere else, really.

MJ: There’s nowhere like New York City!

EC: Absolutely. I love the city in the summer because there's so much happening all the time on every single street. And it's incredibly exciting. You go downstairs and there's a super interesting woman who I've written a lot of poems about named Dolores. She came to New York from the South when she was 15 years old. She's had an unbelievable life in the music world in Harlem. And she sells things on the street across from my apartment every Sunday at the flea market. And she's 87 and she just self-published her memoir, which is fantastic. I really never find people like that anywhere except here. But I will say that what inspired me to write this book was upstate New York because there are amazing people there, too.

MJ: Of course, they’re just more spread out.

EC: Yeah, they're more spread out. My little town has less than 500 people.

MJ: That’s so small! So how did you get into poetry? Every medium of writing is a different skill.

EC: That's absolutely true. But all of us who write love language and that's what ties us together. And I know, having been teaching classes my whole life, that people who write about anything at all, even medical writing or course text, love language. That's a connecting point for us that other people don't have. And it's a really nice connecting point, too.

I had a literary agent in 2014 who ran a very large agency that had a social media division. The social media division was run by a woman who really knew an enormous amount about how to communicate your message in the world of social media, which I know nothing about. And that woman said, You really have to start a blog and the blog has to be accessible to large numbers of people.

So I started something resembling a blog. And not that long afterwards, I thought it would be a real challenge for myself to try and write a poem a day. The way jazz musicians play and play and play and play and play until they play something they love. I thought, I'm going to do that, too. It's been super interesting to be able to write a poem a day. And when Substack started a few years ago, I joined and started posting a poem a day on a Substack called OverheardEC.

MJ: Wow! You’re still writing a poem every day? After almost 10 years?

EC: I write one every day and I have a real audience. And the real audience writes to me all the time, too, which I love. They say, I like this or I don't like this. But it's been a terrific thing.

MJ: Do you publish the daily poems in your books?

EC: I am going to do a large book of the Overheard poems. Not all of them from all these years, but a bunch of them. The book that's coming out in the fall has some of those poems, but also some stories. It's a mix.

MJ: That's incredible. It's lovely to be able to do so many different things.

EC: Well, we all can. We just need the opportunity. And we just need to understand that we all can. That's the thing about teaching writing in this little library in Cairo, New York. My class is a very big mix of people: a guy who owns a hardware store, a woman who works at CVS, a couple of people who actually earn their living writing. There’s a woman who's a hospice worker and gospel singer. You can see when you're in a class of people so different from each other that everyone really has something to say. And when I think about the through line in my own life, the thing that connects the work that I've done all these years is that. Everybody has something to say. It's fantastic to have the opportunity to figure out how that can happen.

MJ: That’s so interesting. And where does the name ‘Book Doctor’ come from?

EC: My second published novel is called Book Doctor. And it's a book about how everyone wants to write a book.

MJ: Does everyone want to write a book?

EC: Yes. Huge numbers of people. In high school, I was an office temp at the Yale School of Art and Architecture. And I was working for the dean of the school. He was the first person who said to me, I really want to write a book. So I helped him and that was the first book I ever worked on. And since then I've helped hundreds and hundreds of people write books. Maybe not every living human, but a lot of people really want to write a book. It's exciting to have a book. It's a way of being permanently in this world. It's very, very exciting.

MJ: It sounds exciting! How many books have you published?

EC: Well, it depends how you count. My first book was a novel, No Charge for Looking, about Jews and Arabs and Israel and Palestine. I did a book with Roz Chast called Don't Mind Me, And Other Lies Jews Tell. I did another novel called Book Doctor and I did a book with many photographs called Unseen America. I published three books of poems and then I've done a couple of little books with other people that we self published ourselves.

MJ: That’s a lot of books!

EC: It's a lot of books. And the new book has taken me a hundred million years. It's really taken me a long, long, long, long, long, long, long time. I started it really when we moved to upstate New York 37 years ago. It's not a long book, it's a short book, but I wanted to capture what I loved about this place and how we shouldn't be tribal, we should be inclusive.

MJ: That’s an important message.

EC: I think it is, particularly today. We dismiss people because they don't think the same way we do. And that's such a mistake. That's such a mistake. I mean, in my case, it's maybe a little easier because nobody ever thought the way I did. I didn't expect that people were going to think the way I did. But it's a mistake. It's really a mistake.

I grew up outside of New Haven, Connecticut, in a factory town called Ansonia. And people there were different from each other, too. And it's interesting because some of those people who went to grammar school with me read my poems every day, even though we grew up so differently from each other.

MJ: That’s a good sign! Even though the world is so polarized right now.

EC: And it's my goal to try and help that a tiny little bit. A book doesn't help very much, but a tiny, tiny little bit.

More from The Journal

Hannah is Going With the Grain

Talking local, sustainable grains with Hannah Smalls, Executive Director of the Northeast Grainshed Alliance. She shares her path to the organization and what this dynamic community is doing to nou...

Read more

Digging In with Allison Turcan

In conversation with the tireless local food advocate and farmer, Allison Turcan. She shares the story behind her creation of D.I.G. Farm and the Westchester Local Food Project.

Read more